About Qanuns

قانون (Qanun) means "law" in Arabic and probably derives it's name from the Greek "κανών"(Kanon) meaning "rule". It was most likely given the name because in traditional ensembles it lays down the law of pitch for the other instruents and the singer. The Qanun is known to have been a part of Middle Eastern music since at least the 10th century. It's widely believed to have descended from the ancient Egyptian arched harp. Altough it's exact origination is not known there are local legends attributing it's creation to Ibn Al-Farabi. Farabi was a philosopher born in a village called Wasij (near Farab, Turkistan) in 870. Al-Farabi wrote a rather extensive ammount on music theory in both Arab and Persian classical music. His works include a book titled 'Kitab al-Musiqa al-Kabir (Book of Great Music)' and a treatise on therapy called 'Meanings of the Intellect' which addressed music as a form of therapy. He was know to have played and invented several instruments and was such an accomplished player he could make his audience laugh or cry at will.

The Qanun entered Europe in the 12th century tthrough the Andalusian courts and was known in Spain as the caño. In France it was known as the Canon, in Germany the Kanon, and in Italy as the Cannale. It may have been introduced to other parts of Europe by way of returning crusaders as well. Somewhere between the 14th and 16th centuries it bcame known in Europe as the Psaltery or Zither.

In the 14th century the Persian treatise 'Kenzü’t-Tuhaf' contained a diagram and written description of the Qanun, along with other instruments. This diagram and description included detailed measurements depicting a half trapezoidal shape. It also specified it had sixty-four strings tuned in sets of three. Abdulkair Meragi, the great composer, virtuoso, and theoretician described the Qanun in his 'Câmî’u'l-Elhân fî ‘Ilmü’l-Musiki' and other treatises as well. Up until the 15th century it was played upright resting against the players body but after the 15th century it was played lying on the lap of the player.

The Qanun had come into use in Ottoman music no later than the 15th century. It was during this time that it underwent a number of changes to it's structure and it had smaller and larger variations. It was constructed entirely out of wood and had metal strings. The Uygur Kalun is the only modern instrument resembling this. By the 16th century instruments resempling Qanuns can be found in Persian miniatures. The shape of the Ottoman Qanun in the 17th century is not precisely known but by the 18th century Ottoman Qanuns were largely the same as the modern Qanun. The Qanun had fallen out of fashion in Iranian music of this time so the changes leading to it's modern form are believed to have been carried out in Turkey, Egypt, and or Syria. Levni did not illustrate any Qanuns in his miniatures but Hizir Aga illustrated a modern Qanun in his 'Tefhîmü’l Makamât' which is estimated to have been written between 1765 and 1770.

During the reign of Sultan Selim III (1789-1807) there were no records mentioning Qanun players however immediatly following during the reign of Mahmud II (1808-1839) records mention Qanun players. In the 19th and early 20th century, the Qanun was popular but was most often played by women. It was extremely poular in Istanbul and a professional music ensemble had to include a Qanun. In 1922 Rauf Yekta wrote a piece on Turkish music for the 1922 edition of Albert Lavignac's 'Encyclopédie de la Musique et Dictionaire du Conservatiore'. Yekta indicated the implementation of Mandals to control the micro-tone tuning dated to 30 some years prior to his submission. This would place the final modern adjustment of the Qanun to include mandals around the 1880's.

The Qanun itself consists of a large narrow trapezoidal soundboard. It is usually constructed out of several woods although Rosewood and Ebony are quite common. Strings are stretched over a single bridge which sits over fish-skins on one end and is attached to tuning pegs on the other. Micro tuning is accomplished on the Qanun by using a series of mandals (or orabs/urabs) on the end near the pegs. There are essentially two types of modern Qanuns, the Arabic and the Turkish. Arabic Qanuns can vary in their exact measurements but Turkish Qanuns tend to be uniformly the same size. Arabic Qanuns are usually larger and heavier than the Turkish and are generally tuned to a lower range of pitches. The Turkish Qanun usually measures about 38 inches (83.6 cm) on it's long side and 13.5 inches (29.7 cm) on it's short side. It's width is 16.5 inches (36.3 cm) which gradually tapers off to 4 inches (8.8 cm) at the narrow end. Arabic Qanuns vary in easurments but are generally a little larger. Arabic Qanuns usually have five skin insets and five pillars to the bridge while Turkish Qanuns have four. The bigest difference in the Arabic and Turkish Qanuns are the string courses and number of mandals. The usual configuration of strings is 26 courses with 3 strings per course Arabic Qanuns genrally have four mandals per string while a Turkish Qanun has 7, reflecting the relative complexity in Turkish intervals.

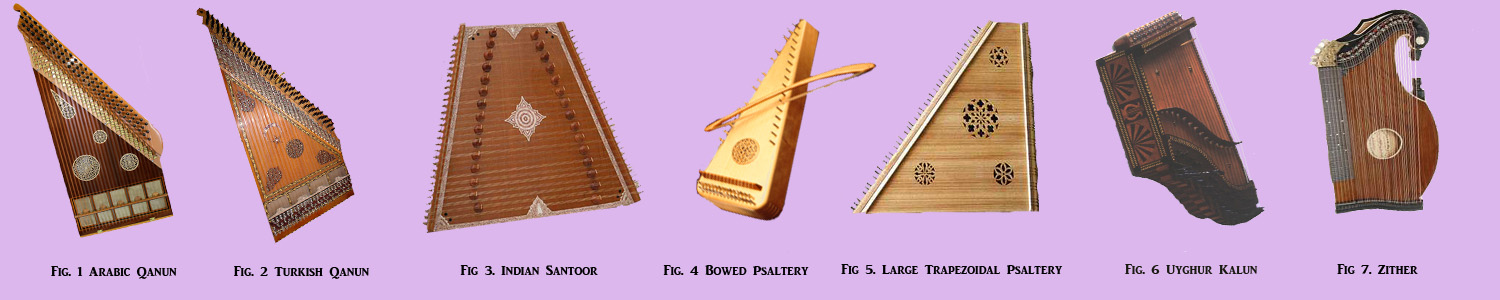

Here are some examples of the different types of Qanuns and other Zither like instruments (if the text is too small, right click the image and select "view image"):

If you're looking for how to care for, tune, or repair your Qanun be sure to check out the Care of Qanuns page. If you're ready to jump right in and learn how to play be sure to visit the How to Play the Qanun page. Want to hear what the Qanun sounds like? Here's a clip of Bassem Alkhouri demonstrating the Qanun.